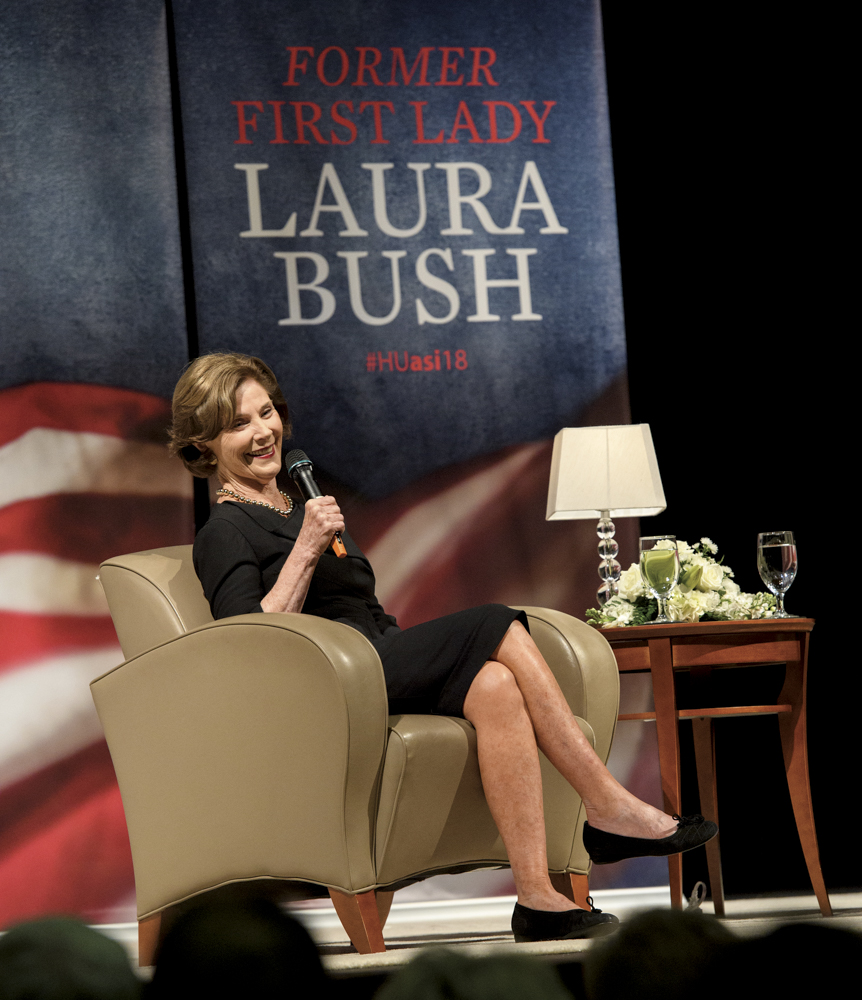

On the evening of April 16, former first lady of the United States Laura Bush captivated the full house in George S. Benson Auditorium. The former school teacher, former first lady, and now grandmother was the final speaker of the 2017-18 American Studies Institute Distinguished Lecture Series.

Laura was the fourth member of the Bush family to address the Harding community. Her husband, George W., and her in-laws, George H.W. and Barbara, were previous ASI guests.

University President Bruce McLarty followed her speech with a Q&A session. She shared anecdotes from her time as first lady, her life as a grandmother, and her life in Dallas post-White House.

“As for me, it’s come to this,” she said in her opening remarks placing a Laura Bush bobblehead doll on the podium. The bobblehead, she said, came from the gift shop of the Constitutional Center in Philadelphia just a few weeks after President Barack Obama’s inauguration.

“It was on the clearance shelf.”

The audience’s laughter and three standing ovations were clear signs of the love for the former first lady whose grace and strength are built on humble beginnings and a strong sense of family.

The following excerpts from her memoir Spoken From the Heart and ASI speech give a glimpse into these formative experiences.

After a mislabeled letter to home bounced back, young Laura thought her parents would forget to pick her up from Mitre Peak. Of course, they did not. She later became an avid camp lover, but as for her first year at Mitre Peak, home was all she could think of.

Her love for home undoubtedly came from her love for her parents.

Harold and Jenna Welch, “Mother and Daddy” as they were more affectionately known to their only child, made Midland a memorable place for their daughter — despite its scorched earth and wind.

“It helped to be fearless if you lived in Midland,” Laura wrote. “What Midland had by the early 1950s were oil storage tanks and junctions of vast pipelines that carried petroleum and natural gas miles away to more populous areas. Sometimes there would be fires at the storage tanks, explosions followed by big, rushing plumes of flame that turned the sky a smoky red. The incinerating heat would pour into the already scorched air and sky.”

Her parents helped curb the harsh elements of the town — wind and sand that gave way to the sense of hardship that lived within the residents there. The Welches were all but ordinary to Laura. Her detailed memories of her parents are evidence of her deep adoration of the two.

Her mother’s attention to detail in “the Big House,” one of many homes the family lived in because of her father’s work in the construction business of Midland, left memories of turquoise everything — refrigerator and countertops in the kitchen and bed skirts and bedspreads in the bedrooms.

Her father’s favorite meal was chicken-fried steak, gravy and homemade french fries (made, of course, by her mother, Jenna). He kept patches of onion, squash and chilies alive in the backyard because, according to Laura, her parents grew up rural enough to know most everything you eat in high summer and early fall could come “off the vine or out of the field.”

“But Daddy said that he loved his Jenna’s cooking best of all,” she wrote. “He wasn’t like the other downtown men who ate lunch out at a restaurant or ordered at the counter at Woolsworth’s. And so Mother would listen each day for his car to come humming up the street right around noon.”

Her parents’ love for one another perhaps came out of example from her grandparents — specifically her mother’s parents whom she loved and admired dearly.

Hal and Jessie Hawkins lived along the Rio Grande in El Paso, Texas. They were both originally from Arkansas (then moved to Texas), but Jessie’s parents were from France.

Laura had a strong love for Grammee, her maternal grandmother, who was only 21 when Laura’s mother was born.

“I loved my Grammee with a particular devotion,” she wrote. “Not only did she make my clothes and doll clothes, but she also built my doll furniture by hand, little couches covered in lush brown velvet with tiny navy velvet pillows edged in rich gold braid. I thought they were the most elegant things I had ever seen.”

When she visited her grandparents in the heat of the Texas summer, she would forget the summer’s unpleasantries. She was mesmerized by her grandmother’s intricacies — her collection of rocks and disobedience to the standard dresses and aprons of the local women. (Grammee would wear pants, hats, gloves and long-sleeved shirts to combat the sun.) Her grandmother, she believed, could do anything.

At night, her grandmother would lie with her as the desert breeze put the two to sleep in the guest bedroom.

“Grammee, whose own childhood has been cut perilously short, lovingly created so much of my own,” Laura wrote.

When a longtime incumbent of their West Texas district announced his retirement, the seat became open, and the Bushes took to the towns of the 19th District. This would be just the smallest glimpse into the campaigning they would do together.

In her book, Laura described campaigning in the communities of the dry Texas-scape as “retail politics.” They shook every hand and knocked on every door.

Back roads and highways up and down the panhandle gave way to the stories of everyday people and everyday life. George’s Oldsmobile Cutlass became the place where the two grew in marriage and learned the lay of the West Texas land. They learned more of one another while politics became an early staple of their marriage — taking to the congressional campaign trail after just one year of marriage.

“We never worried that any long-buried fact about the other person would appear and surprise us. From the start, our marriage was built on a powerful foundation of trust,” she wrote. “We had been cut, as it were, from the same solid Permian Basin stone. So we drove and we talked and we laughed and we dreamed in the front seat of George’s Oldsmobile.”

The 19th Congressional District of Texas was traditionally Democrat, she recalled in her book, so the newly married couple had their work cut out for them. The first campaign found them in small towns across the district, usually next to a pot of coffee and plate of cookies. Though beside him for the campaign, Laura said she would never give a speech. And George told her she wouldn’t have to.

But a campaign stop in Levelland, Texas, gave way to a broken promise — the only promise George has ever broken, she wrote. Her husband was not able to make the stop, and she had to speak for him. Alongside other candidates and in front of the crowd, she made her case.

“When I finished speaking, I wasn’t particularly eager to do it again, but it also wasn’t nearly as bad as I had anticipated,” she wrote. “In fact, it wasn’t much different from reading a story to my students. … Suddenly, all my old story hours had a very different use. Out on the campaign trail, I discovered that politics is really about people, and even though I was more reserved than George, I liked meeting the oilmen, the farmers, the moms, and the store owners.”

Their stories took her back to her days as a school teacher. The stories meant the most in both cases — campaign trail or classroom.

Ultimately, their campaigning for the 19th District did not pay off. George lost in the general election, and the two returned to life in Midland. George went back to work in the oil business. Laura started to set up their new home — hopeful to fill their empty spaces with cribs and strollers.

Time at home and hopefulness for a family reaped discouraging results. A mailbox constantly filled with shower invites and birth announcements, and countless baby gifts bought did not help the scenario either. Hopefulness led to sadness, and milestones passed still with no children.

“For the loss of a parent, grandparent, spouse, child or friend, we have all manner of words and phrases, some helpful and some not. … But for an absence, for someone who was never there at all, we are wordless to capture that particular emptiness,” she wrote. “For those who deeply want children and are denied them, those missing babies hover like silent, ephemeral shadows over their lives. Who can describe the feel of a tiny hand that is never held?”

The Bushes spent two years back at home off the first campaign trail, and in April 1981, Laura learned the news they had been hoping for since their return home. She was pregnant.

They welcomed twins Barbara and Jenna Bush (named after their mothers) into the world Nov. 25, 1981.

In late 1988, the Bushes moved to Dallas. George and an oil business partner put together a group to buy the Texas Rangers. Laura, while a fan of baseball, took less stock in the game and more stock in their new Dallas home.

She became involved in Dallas-area life. She was a PTA and carpool mom at the elementary school where Barbara and Jenna attended. Chairing committees for the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, she helped with fundraising for the nonprofit. The Dallas Zoological Society and Aquarium invited her to serve on their board.

Laura became an integral part of Dallas-area society, but their sights were never set too far from Washington where her father-in-law was now serving as president. Laura, George, Barbara and Jenna’s names became regulars on the invite list for state occasions.

In November 1992, her father-in-law lost his re-election to Bill Clinton, and just one year later, her husband announced his candidacy for the governorship of Texas.

It seemed she would be making a few more speeches — a stark contrast to that promise of George’s first campaign. Southwest Airlines became a friend for travel and a dear friend for getting George back home in time for dinner during the hectic campaign schedule.

Laura, though remaining primarily in Dallas to take care of Barbara and Jenna, took to the statewide campaign trail, too.

“I did events as well, speaking to women’s groups all around Dallas and sometimes joining George on the statewide hops,” she wrote. “And when I wasn’t his surrogate, I was the mother of two 11-year-old girls, with their myriad of activities, friends and preadolescent dramas.”

Just six years after moving to Dallas, Laura and the family packed up and moved again, this time to occupy the governor’s mansion in Austin. As first lady of Texas, Laura chose to sharpen her focus on education — a natural fit for the former teacher. She also made Texas’ Department of Family and Protective Services a high priority; when they first moved to Dallas, she began working with the agency, and now as first lady, she continued support and reform.

Although first lady of the second largest state in the nation, Laura was able to maintain a certain sense of normalcy while in Austin.

“Barbara and Jenna love to tell the story of the time we were standing in a checkout line at Walmart in Athens, Texas, near our little weekend getaway lake house, and a woman kept staring at me,” she wrote. “Finally, she said, ‘I think I know you,’ and I replied, ‘I’m Laura Bush,’ as if, the girls liked to point out, of course she would know who I was. Her answer was ‘No, I guess not.’”

In 1997, conversation had sparked about George’s interest in the presidency, and that sense of normalcy was soon relegated.

Laura recalled one of their final visits and the sweet sense of joy that never escaped her parents.

“Grinning, laughing, they turned to each other, eyes catching, and then they looked up again,” she wrote. “They were happy. No sadness ever unraveled their happiness. In the tiniest thing they could find joy. That morning it was our cat, Cowboy, who had climbed up on our roof. And they entered the kitchen smiling.”

A pure adoration that started early continued forever. Through her father’s failing health, she still saw the man who shaped, molded and reassured her under the incessant sun and heat of West Texas.

Harold became housebound. His mind eroded. At a doctor’s visit, he couldn’t recall the most recent president — Laura’s father in law. All the while, life for the Bushes progressed and campaigns turned into terms. Barbara and Jenna grew up. Laura tried to balance both sides of the weighty scale.

Her beloved father died April 29, 1995.

The burden of grief rested heavily on her mother, the second pillar of influence and strength in Laura’s life. She watched as it took years for her mother to move past her father’s passing and into well-being.

“Daddy’s funeral was on a Monday,” she wrote. “Later that week, I was back in Austin. My days were crowded; I did not have too much time to dwell on memories until Christmas when we played our home movies of the girls as babies, and Daddy’s face and arms flashed across the frames. And for years afterward, even now, I would dream of Daddy. And in my dreams, he is well.”

The announcement, however, did not come without reservations from Laura. She had seen the way the 1992 race had pressed their family and her father-in-law.

“I sat beside George, smiling,” she wrote. “But I had been late to sign on to his decision to run. … I believed in my George, I love him, and I knew he would be a great president. It was the process in which I had far less faith.”

Iowa was their very first campaign stop in 1999 like nearly any other candidate running for the presidency. The primary state and all of America soon became familiar to the family, but they tried to seek relief back home in Texas as often as they could while airplanes and hotel rooms became commonplace for the Bushes.

After a primary win and a too-close-to-call general election against Vice President Al Gore, George W. Bush became the 43rd president of the United States (after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled a Florida recount had violated the Constitution), and Laura became first lady — again.

During her time as the nation’s 39th first spouse, Laura spearheaded multiple efforts.

Like her time as first lady of Texas, education was at the top of her list. She traveled the globe advocating for literacy and education to create stable democracies. Women’s initiatives, both foreign and domestic, filled her time as well. Events like 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and the war in Afghanistan marked her time alongside her husband in the White House.

Just under a year into the presidency, 9/11 left the Bushes with a nation turned on its head. Hard days left Laura with emotions and attitudes from her husband that she had not seen before.

“I had originally fallen in love with George due in large part to his sense of humor,” she said to the Benson crowd. “But there were days when there was no laughing and no wise cracks — when I looked at his face and saw the gravity of the choices he had to make, when I saw tears in his eyes after visiting the parents and spouses of the men and women who had been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Not everyone had the opportunity to see this side of George W. Bush.”

When the Bushes left Washington on Obama’s first inauguration day, Laura said she departed with a sense of pride for the nation, and she told the audience of her love for the American people.

“When you live in the White House, you live not just with the ghosts of presidents but with the echoes of citizens holding this government to account,” she said. “Living there certainly does not make you infallible, but it consistently brings you comfort.”

Today, Laura and George are back in Dallas where they live a “normal” life according to Laura. They are heavily involved in the work of the Bush Institute where they work on a number of issues. In particular, Laura still heads up multiple women’s and educational initiatives.

Their most cherished post-White House duty, however, is spoiling Mila and Poppy, their granddaughters.

“Mila and Poppy are perfect,” she said. “And our daughter Jenna and our son-in-law Henry are thrilled — although they have to be careful of being trampled by George and me in our rush to get our hands on the babies.”

From Laura Welch to Laura Bush and from first lady of Texas to America’s first lady, Laura has held many titles — including Mimi Maxwell, a name she said her grandchildren, for no apparent reason, bestowed upon her (and George just wants the grandkids to call him “Sir,” Laura said).

The woman of many titles, many stories told and many miles traveled left the Benson crowd with a final charge, calling each person to service — whether or not they are addressed as “Mr. President” or “Madam First Lady.”

“It’s not only the president’s job,” she said. “It’s the job of any American — Republican, Democrat or Independent — who has an urge to take a stand and make a difference and who is willing to step up … to face the banter, humiliation or even mortal danger. The greatest honor of being first lady was having the chance to witness every now and then, not just my husband, but all of America facing up to fear and shattering change and standing proud.”

Written by Kaleb Turner; photography by Jeff Montgomery