Professor of Chemistry Edmond Wilson has been working for Harding since 1970. He has taught almost every class in the College of Sciences’ department of chemistry. When he was a senior in college, he received damage to his ear from being thrown into the Hog Pond, a tradition for graduating seniors. He has photographed more than 200 weddings of Harding students and faculty. He enjoys traveling and music. In his spare time, he does research, and he has secured approximately $1.8 million in grants for the University.

AS A FRESHMAN at Auburn University, I went to the library and checked out Isaac Newton’s famous work Principia Mathematica. I tried hard to read and understand but had to give up. It was beyond my comprehension. I felt better when I learned that Newton wrote it originally in Latin and used obscure language deliberately to avoid being challenged about the content.

Dr. Ed Wilson grew up in Alabama. His dad was in the military, and when the subject of education came up, Wilson’s dad made him promise two things. “He said, ‘You won’t get married until you graduate from college, and you will go to college.’ I did both,” Wilson says.

His dad said they could afford to send him to either University of Alabama or Auburn University.

“He said he personally liked the University of Alabama, so I picked Auburn.”

Wilson received his bachelor’s degree at Auburn and says he learned a lot from professors who challenged and encouraged him. He then went on to University of Alabama where his dad had wanted to enroll in college. While working on his advanced degrees, Wilson was able to really delve into a variety of areas of chemistry and learn about what he liked and was good at.

“Because we had to have a major and two minor fields, a large number of classes, and many comprehensive exams, I found myself proficient in a very wide range of chemistry topics. This helped immensely as I taught classes in every area of chemistry that Harding offered at the time except for the one-year organic chemistry course whose star was the legendary Dr. Don England.”

While at the University of Alabama, Wilson started working on his Ph.D. He designed, built, calibrated and used a thermometric titration calorimeter to mea- sure the amount of moisture in samples. Though he did not publish the moisture determination method, Wilson says a company that sells titration calorimeters picked up the idea and published an article about the process, which later became known as the Sadtler-Wilson method of moisture analysis.

“Sanda Corp. uses the Sadtler-Wilson Moisture Determination as a selling point for their calorimeters. Later on, I became quite close friends with the CEO of Sanda, Traude Sadtler, and she loaned me one of her calorimeters to do some research at Harding. Because of this, I was able to publish an article with one of my students using the method I developed for my doctoral thesis.”

After finishing work on his Ph.D., Wilson went to the University of Virginia for a post-doctorate fellowship where he researched for two years and published nine papers. After that time, he began looking for jobs teaching chemistry at a university. After a suggestion from his wife, Elizabeth, Wilson began writing to Christian schools, and at that time, Harding was in need of a physical chemistry teacher. Wilson came to Harding in 1970.

“At first, I tried to do some research with the students, but we didn’t have any equipment, and I got terribly discouraged because I couldn’t do anything without equipment. I took up woodworking for a while.”

Wilson worked with Dr. England to secure a grant that would enable the department to purchase equipment. Through the grant, they obtained equipment such as an NMR machine, an atomic absorption spectrometer, and a high-resolution infrared spectrometer.

“We got the basic instrumentation to do a whole lot of things and provide a good education for our students. I was able to start working with the students to do research, taking them to conferences, and so on. It’s just built since then.”

ONE TIME, I HAD TAKEN the students in a van to Dallas to a chemistry meeting, and I wanted them to see the Galleria Mall while there. Well, this was before GPS, and we were lost, and everyone was frustrated and hungry. People started yelling at each other, and there was some crying, and I said to them, “This is great! We’re now acting like family!” It was a great trip. I thought I knew where the Galleria was, but it turned out to be a big office building.

“I try to give them a sense of community by taking them on as many science meetings and trips as can be worked into a crowded school year,” Wilson says. “I treasure the trips together with the students. There is always something special about spending time together on a trip.”

One such trip is an annual visit to a NASA facility in San Jose, California. Students have the opportunity to tour the facility, walk through laboratories, meet scientists, and attend speaker presentations or seminars. The purpose of the trips is to build infrastructure with NASA, and Wilson and his students make connections and build relationships with scientists that will sometimes lead to internship opportunities or visits and presentation to the Harding community.

“One day, I told my wife, ‘You know, it’s really neat that I can go to these NASA facilities and get to meet all of these people.’ And she said, ‘It’s also neat that they know about Harding.’ And they do. If you call them up, they know all about Harding. They’ve been very helpful and very supportive.”

MY WIFE AND I CELEBRATED our 50th wedding anniversary in August of this year. I have always loved her dearly, and my love and admiration continues to grow for her each day. Without her support and encouragement, I could never have done the things I have been able to do.

Elizabeth is the former chair of the department of family and consumer sciences and has also received NASA funding for students to carry out research in space nutrition. Twice, she was awarded funding to take 25 high school teachers to Johnson Space Center in Houston for them to learn about food science and nutrition for space missions and growing crops for extended space missions.

“All of us enjoyed those trips,” Wilson says. “My wife and I especially treasured being with the high school teachers and learning so much more about the space program as it applies to human space travel.”

ONE TIME, DR. ENGLAND was lecturing on keto-enol tautomerism, and one of our students just burst out laughing. Dr. England said, “What is so funny?” The student replied, “I thought you were speaking Chinese!”

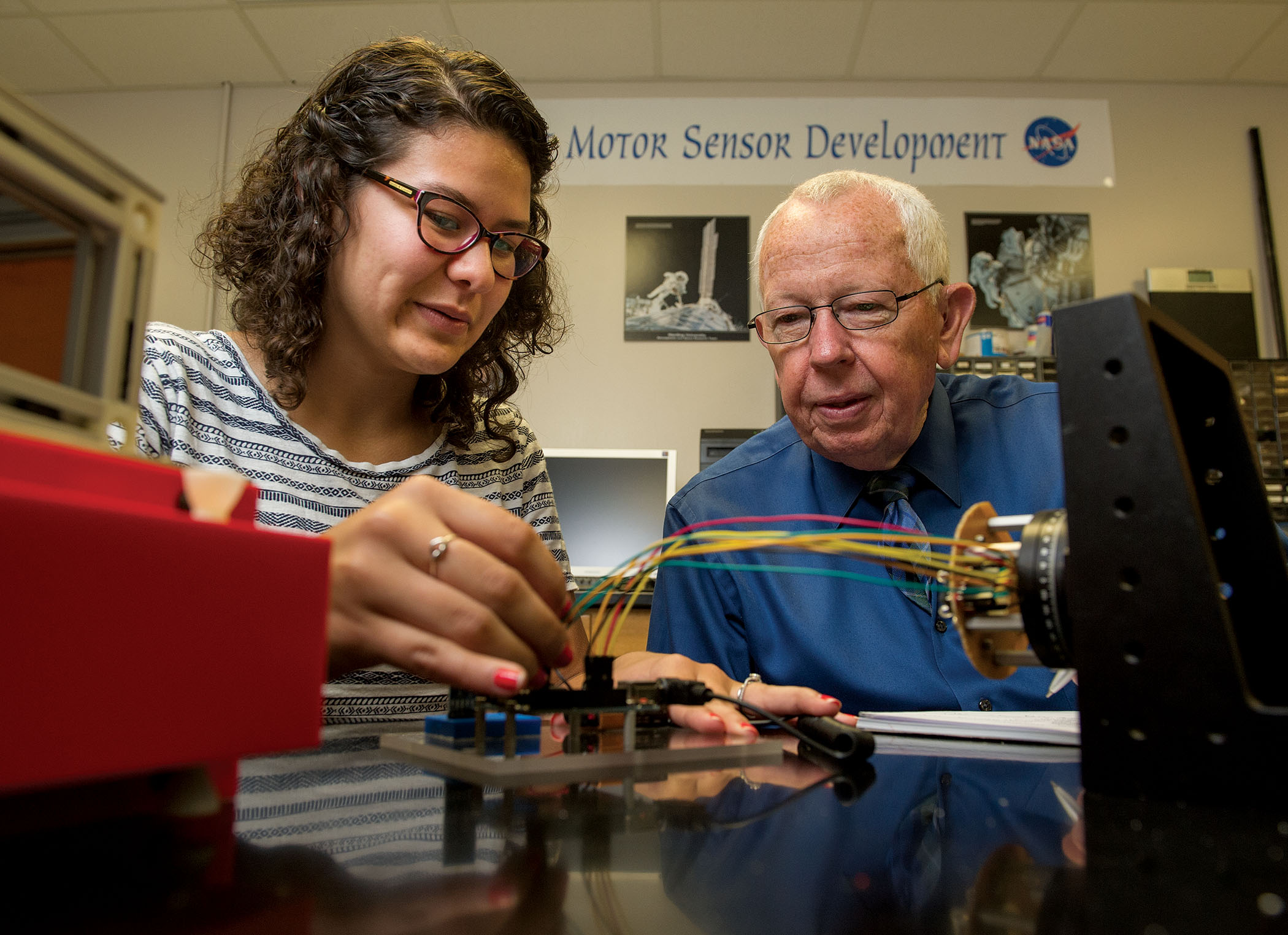

Wilson is as comfortable in the classroom as he is working in a NASA lab. He says he loves working with people, and he would much rather perform research with students and fellow scientists with whom he has made relationships. Where many university professors in the field of sciences often select one or two students to work alongside them in research pursuits, Wilson typically takes on 10 or more.

“I don’t like turning people down, and I like putting them to work,” he says. “I love working with people, and I’ve got lots of ideas. We’ve got money to give them scholarships and trips to NASA facilities, so we go and do it and have a good time.”

In the past 25 years, Wilson has mentored 164 students from a variety of science areas working on a wide range of research projects. Alongside his students, he has published almost 40 articles for scientific journals. He also keeps a record of every student he mentors and details his or her research accomplishments during the year.

“I’ve been very fortunate to have good classes. I really like the freshmen students because they’re pretty easy to deal with for the most part, and I really like the seniors because they’re laid back, and they don’t get excited about everything. The sophomores and juniors sometimes get crazy.”

WE HAD A SPEAKER come to Arkansas and bring a NASA Rover with him to give a talk at the Aerospace Education Center in Little Rock. We carried the Rover around in the back of the car. You can’t do that anymore, but it was a $23 million rover. My wife said, “Well what happens if we have a wreck?” The speaker said, “Don’t even think about it.”

In his 45 years at Harding, Wilson has managed to attract $1.8 million in grants for the University. He says the highest point for him was receiving a $670,000 grant from NASA to build a laser spectrometer for Mars.

“Several years ago, I became interested in diode lasers, you know, the kind that are used for laser pointers,” he says. “While trying to think of an application for these interesting devices, I decided that I could make a spectrometer with one of them. I felt that if I wanted to search for life on Mars using a laser instrument, I might be able to get funding from NASA for the project.”

Wilson formed a team with two other scientists to seek funding for the project and arranged a trip to Jet Propulsion Laboratory to pitch their idea to Mars researchers. Wilson was last to present, and he talked about his ideas for building a device that would be able to find trace gases that microbial life might emit if there were such microbes living in warm, damp places underground on Mars.

“When I finished, one of the top robot experts at JPL, began to tell me everything that was not good about my plan. I felt badly and saw our chances for NASA support going down the drain. When he finished, he looked me squarely in the eyes and said, ‘I think you have a good idea, and I will support you!’ That was one of the big moments in my career. With valuable contributions from each member of the team, we were able to submit a proposal to NASA that al- lowed us to receive $670,000 over a three-year period to develop our plan.”

It took Wilson and his team 13 years to develop the instrument, and they are currently planning field testing and will soon acquire additional funding to bring the project to a higher level of readiness. Funds for the project have provided materials, supplies and research scholarships for many Harding undergraduates to work on the project and opportunities to visit with professionals at NASA centers and present reports and papers at meetings.

Wilson works closely with the Arkansas Space Grant Consortium to obtain grants used for scholarships, equipment and other research materials. He also works with other researchers and makes connections with professors across the country. In 1997, Wilson met a scientist from Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was head of the organization’s atmospheric chemistry program. Wilson thought this field might be a good area of research for Harding, and that led to an internship during the summer when the first NASA Rover landed on Mars.

“I try to go and meet as many people as I can and talk to them because I’m interested in what they’re doing. I spent five summers in Fayetteville, Arkansas, working with Dr. Bill Durham on research. We made molecules that attached to proteins to understand their structure better. I learned a whole lot from that.”

OUR DESIRE IS to have a fleet of satellites flying around Saturn’s moon and study the atmosphere there. The atmosphere on Titan is methane. It rains methane, it snows methane, and they have lakes of methane. We hope to continue to get money to build our program to be the first team in Arkansas to put up a satellite. NASA really wants every state to have a presence in space.

For the past two years, Wilson and his students have been working on a project to launch a fleet of satellites into space, which has never been done. The satellites they are using are called nanosats due to their small, cubic size measuring 4 inch by 8 inch by 12 inch.

“The engineers who designed the rockets to take satellites into space designed them to carry a heavier load than what they carry as a safety buffer. The satellites our students are making weigh 10 pounds or less. We are allowed to get a piggyback ride when they send up a big satellite, and we can put our little satellite on it and have it shot off.”

Wilson suggests that a group of smaller satellites could possibly do more than one big satellite, and if a satellite experiences problems, the others flying with it can recover and pick up the slack. The project idea came to Wilson after meeting a fellow scientist in Fayetteville, Arkansas, who is a Titan expert.

“We were trying to pitch our proposal to go around the earth and measure the atmosphere of the earth, but everybody and his brother is doing that, so we decided to go for something a little different hoping it would help us get our grant. People want to send a mission to Titan, but a small satellite mission would be tremendously cheaper than the ones that are up there right now.”

Harding’s nano satellites program received its second year of NASA funding November 2014. Wilson says that when they receive full funding for the project, the fleet of satellites could be flying around in space in one or two years.

“It is so exciting for us at Harding to get to participate in these wonderful space exploration projects. I can’t help but dream about using our satellites, because of their compact size, for missions to the moon, Mars, and even to further solar system bodies like Titan and Europa. The Harding administration, from top to bottom, has been very supportive of efforts to establish a first-rate research facility here at Harding. I feel so blessed to be a part of this great university.”