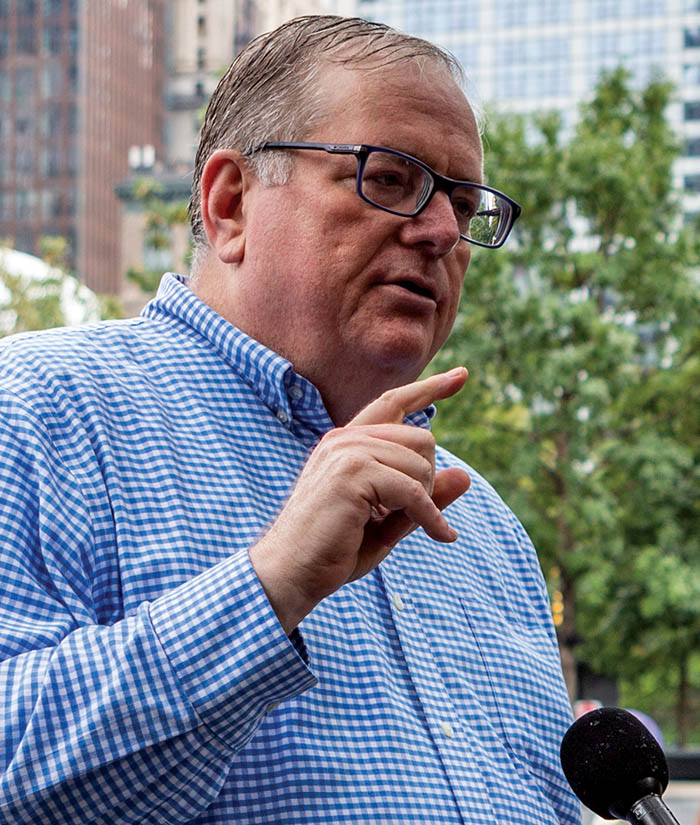

Distinguished Professor of Communication Jack Shock went to New York City 20 years ago to serve as a public affairs specialist at 9/11 and returned this fall to provide a real-life classroom experience.

In the 2002 winter issue of this magazine, I wrote about my ground zero experiences working with the American Red Cross crisis communication team. My job was to help manage media requests immediately following the events of 9/11. My notes from that story remind me we were balancing media questions about airstrikes in Afghanistan and anthrax attacks with providing care and comfort to the first responder heroes.

“One afternoon I managed to find an electrical closet where I could escape the chaos and use my cell phone to teach my class via speakerphone. I loved being able to share with my students what I was seeing and doing. The 1,200 miles that separated us evaporated as technology transported me back to my classroom for 45 minutes. Their questions and eagerness to learn made me remember why I love being a teacher.”

And suddenly it was 2021 and time to think about participating in the 20th anniversary 9/11 memorial experience. When I realized that many of my current students had not even been born in September 2001, I knew I had to involve them in some meaningful way. The department of communication, in partnership with the Honors College, took 11 students to New York City for the observance.

We spent hours in the 9/11 museum, and I watched students who were toddlers in 2001 dive into the ground zero story before debriefing on the steps of Battery Park, discussing what we had just seen while the Statue of Liberty stood as a silent sentry just across the way. We knocked on the midtown door of Engine Company 54, and a student said, “I was not alive when you lost your friends. Can you tell me about it?” This company lost all 15 firefighters who responded to that early September morning call.

The captain opened the doors and told us we were the first visitors allowed inside in 18 months. Our campus newspaper reporter got an hour long interview with the captain, and the rest of us stood captivated in the presence of these heroes who told us about each of their friends who are now memorialized in bronze on the station wall. We saw the handwritten notes on the call board, detailing the truck positions for that shift. We saw their faces, and we read their names. None of them came back. None of us will ever forget our hour with Engine Company 54.

Even though I was in lower Manhattan on Thursday and Friday of a school week, again I didn’t miss a Searcy campus class. This time, however, I wasn’t confined to an electrical closet using a dying Blackberry and a speakerphone. By using Zoom and related digital technology, it was as if I were with them in the Reynolds Center, or, even better, they were with me on the New York City sidewalks. We had meaningful conversations about art, architecture and street protest, and we interviewed several New Yorkers about their memories of that fateful day.

My teaching maxim has always been “if the whole world is talking about it, we should be talking about it.” If the whole world is there, we should be there. In the department of communication, we try never to miss a chance to pack a bag and chase the story.

When I think of the Septembers of 2001 and 2021, my most nostalgic memories are focused on sharing the experience with my students, helping them grow their skill sets, their confidence and compassion.

Now we’re all back in the Reynolds Center, spending our days doing what we do in classrooms every day. We’re using our September experiences to fuel our discussions and inspire our future. One day the phone will ring again, and we’ll be ready.